By Christopher Vaughan for ASU Magazine. March 2014.

Soaking up knowledge to conserve that most precious of resources – water

When ASU professor Enrique Vivoni brings American students across the border to Mexico, it’s an eye-opener for them. As part of the US/Mexico Border Water and Environmental Sustainability Training Program, Vivoni works regularly with American and Mexican students on both sides of the border to help them gain a deeper understanding of the water scarcity problems in the Arizona-Sonora desert region. When the students see the many water problems that Phoenix has solved but Mexico is still working on, the common reaction is “I didn’t realize we had it so good,” Vivoni says.

When ASU professor Enrique Vivoni brings American students across the border to Mexico, it’s an eye-opener for them. As part of the US/Mexico Border Water and Environmental Sustainability Training Program, Vivoni works regularly with American and Mexican students on both sides of the border to help them gain a deeper understanding of the water scarcity problems in the Arizona-Sonora desert region. When the students see the many water problems that Phoenix has solved but Mexico is still working on, the common reaction is “I didn’t realize we had it so good,” Vivoni says.

Over the last century, Arizona has created hydrological solutions that have allowed us to populate the desert and made access to water a “soft” problem that most people don’t need to think about, Vivoni says. But that is changing. The needs of agriculture and growing populations will more than drain existing water sources in the state. Historical weather cycles and a changing climate will likely make water supplies even more uncertain. And as hard as things get in the United States, the challenges that populations around the world face in securing adequate water supplies only will grow more dire. Some say that eventually water will be more expensive than oil.

ASU finds itself in a unique position, blessed with the position and resources to address the huge challenges surrounding water access, not only for local communities, but also for cities around the world. Accessing expertise in hydrology, the life sciences, geography, engineering, design and law, ASU researchers are tackling the multifaceted issues involved in solving the problem of water security.

“ASU is well positioned geographically for dealing with many of these problems, and we are leveraging our place along the United States-Mexico border region to understand water issues through many of our faculty members,” Vivoni says.

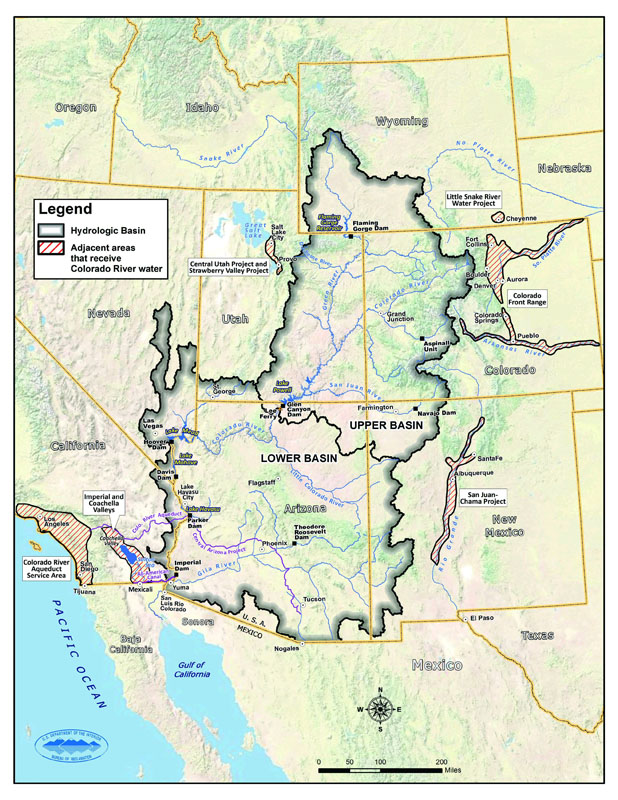

Making changes in the ‘Cadillac Desert’

Professor John Sabo is one of those faculty members studying the problem. As director of research development and senior sustainability scientist at the Global Institute of Sustainability, Sabo knows that communities shouldn’t use more than 40 percent of the renewable water supply to ensure sustainability. “In the region [of the Southwestern United States] known as the ‘Cadillac Desert’ the water use is close to almost 80 percent of the renewable supply,” Sabo says. “We are never going to get to 40 percent; we could get to 60 percent, but it would be costly.”

Just exactly how costly?

“If you cost it out, it’s somewhere between $4.5 billion and $8 billion annually over the next 6-14 years across all seven basin states,” Sabo says. Included in that calculation is an assumption that cities and farms will each become 20 percent more efficient than they are now. “That is not trivial — it works out to between $250 and $875 dollars per year per household,” he notes.

One focus of Sabo’s research is on what amount of water is needed to sustain the natural environment, which is often the neglected third element of the water discussion.

Sabo and his colleagues use the different isotopic profiles of river and groundwater to trace the source of the water on which plants and animals along the river depend for survival. His work has shown the surprising result that it is groundwater, not the surface water that comes down the river, that is providing most of the water for the flora and fauna that exists at the river’s edge.

“It’s said that water always flows toward money, and in the struggle for water between cities and agriculture, the environment always loses out,” he says.

Since water flows toward money, Sabo argues that the only way to protect the river environment is to create new legal and fiscal structures that can protect water for that environment.

“My recent paper is about financing reform that would protect that environment,” he says. He goes on to say that either people will have to rewrite the compact that governs Colorado river water, for instance, or they will have to work within the existing compact to provide the money that buys those water rights and places them in trusts where they are preserved for ecosystems.

“Rewriting compacts is not an option here; trusts are much more tractable,” he says.

Decisions, decisions, decision-making

Balancing the needs of agriculture, cities and the environment will come only from making many such difficult decisions, and each decision will have many “downstream” effects on other human activities. Getting decisions makers the best possible information about water use and future scenarios has been a major reason for creating the Decision Center for a Desert City (DCDC) in the Global Institute of Sustainability.

Patricia Gober, the founding director of the center and a professor in the School of Geographical Sciences and Urban Planning and in the School of Sustainability, was one of those who decided to use the Phoenix area as a case study of how to help people make better decisions about water management. The effort draws from a wide variety of disciplines. There are currently more than 20 faculty co-investigators from the social, behavioral and physical sciences in addition to hydrology and climatology.

“We created a computerized water simulation model that looked at supply and demand for Central Arizona, community by community,” Gober says. “We made it interactive through the use of slider bars to change levels of population growth and indoor and outdoor water use.”

They exposed elected officials and water managers to the model in the Decision Theater, an immersive audio/visual environment, and worked through various scenarios with them to understand how officials balance needs and make decisions. “We also study ourselves,” Gober says. “We tried to learn how scientists engage with decision makers and how we can improve that interaction.”

The simulation continues to be refined. “We are on WaterSim 5.0 now — it will never be finished,” she said.

Learning from each other

The reins of DCDC now have been taken up by Associate Professor Dave White, the current co-director of the center and its principal investigator. “ASU is producing science and knowledge that is not only the best available, but also because of the close collaboration with the decision-making community, it has relevance and salience” in the world at large, White says.

Of most concern to him now in Arizona are the combination of the state’s growing population and the natural variability of the weather, including cyclical dry periods that can last 30 years, plus the uncertain pressures brought on by climate change.

“On top of that, we could have a catastrophic wildfire in the mountains that prevents the accumulation of the snowpack that usually releases water into summer,” said White, who is also a senior sustainability scientist at ASU’s Global Institute of Sustainability. “That scenario is really problematic for me now.”

A key element of the center and its programs is that knowledge flows both ways.

“We learn a lot from the managers of those agencies,” White says. “That knowledge leads to enhanced science on our side.”

Mutual understanding and close cooperation will become vastly more important in the future, White says. Like most researchers working on water projects at ASU, White says he is both pragmatic and realistic about the water challenges we face. Ultimately, the researchers tend to believe that smart research and thoughtful decision-making will head off the worst scenarios and ensure that communities don’t go dry.

“I’m optimistic about our ability to deal with these things,” White says.

Author Christopher Vaughan is a freelance science writer based in Menlo Park, CA

A trade-off paradigm was used to examine priorities in residential water use. A total of 426 participants allocated either a small or large budget to various household water uses. A comparison of allocations across budget conditions revealed which water uses were regarded as most important, as well as the amount of water regarded as sufficient for each use. Further analyses focused on the perceived importance of outdoor water use, which accounts for the majority of the water used in residences. Data indicated that indoor uses, especially those related to health and sanitation, were consistently higher priorities for participants in this study. The finding that residents are more willing to curtail outdoor water use than indoor water use has important implications for behavior change campaigns. Individual difference variables of environmental orientation and duration of residence in the desert accounted for some of the variance in water choices.

A trade-off paradigm was used to examine priorities in residential water use. A total of 426 participants allocated either a small or large budget to various household water uses. A comparison of allocations across budget conditions revealed which water uses were regarded as most important, as well as the amount of water regarded as sufficient for each use. Further analyses focused on the perceived importance of outdoor water use, which accounts for the majority of the water used in residences. Data indicated that indoor uses, especially those related to health and sanitation, were consistently higher priorities for participants in this study. The finding that residents are more willing to curtail outdoor water use than indoor water use has important implications for behavior change campaigns. Individual difference variables of environmental orientation and duration of residence in the desert accounted for some of the variance in water choices.