Mapping the River Ahead: Priorities for Action Beyond the Colorado River Basin Study. March 2014.

A Carpe Diem West Report in partnership with the Center for Natural Resources and Environmental Policy, University of Montana.

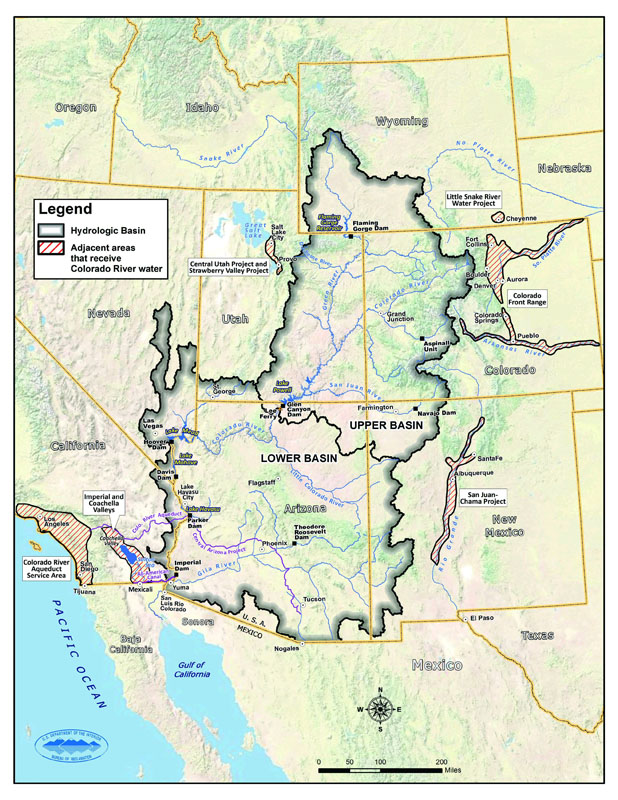

There’s a new way of thinking about water in the Colorado River Basin, and it’s a lot more expansive than the state centered battles of the past. This evolution is timely in light of the formidable challenges and uncertainties facing the 35 million people who depend on the Colorado River from Colorado to Calexico.

In November of 2012, the United States and Mexico signed an historic agreement for cooperative management of the Colorado River that builds upon the long-standing Treaty of 1944. Along with the federal officials who led the U.S. delegation, representatives of the seven Colorado River Basin states and environmental groups actively participated in the negotiation process, and are essential partners in its implementation. No one succeeds in this initiative unless everyone pitches in.

This is not the first agreement that grew from and counts on basin-wide cooperation.

In 2007, the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation adopted Interim Guidelines for managing the operation of Lake Powell and Lake Mead, reflecting terms negotiated by the seven basin states to address potential shortages through a system of shared curtailments in response to specified hydrologic conditions. It did not contradict the Law of the River, but as one state official described the agreement, “we stretched the hell out of [it]”—referring to the collection of statutes, regulations, and policies that govern basin-wide water allocation and management.

In the coming years, such stretching will need to be done far more often, as pointed out by the findings in the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation’s 2012 Colorado River Basin Water Supply and Demand Study (“Basin Study”), which was conducted in collaboration with the seven Basin states along with Indian tribes and a diverse list of other stakeholders throughout the region.

For this report we interviewed 32 Colorado River leaders to gather and assess their candid opinions about priority actions going forward following the Basin Study. Our interviewees—whose names are listed at the end of this report, but whose comments remained anonymous— included current and former employees of local, state, interstate, tribal, and U.S. and Mexican federal entities, as well as people at water supply organizations, conservation groups and other nonprofits, universities, and research institutes. Many of these individuals are actively involved in the Work Groups currently delving into the options highlighted in the Basin Study, with the support of the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation and the Basin states.

All of our interviewees agreed that time is short, the need for action is urgent, and the innovative solutions emerging throughout the Basin should be shared through more deliberate cooperation and partnerships.

This is a time of opportunity. As one leader observed, “The drought ‘turned the light on’ for many people, so they are more open to the necessary steps to move ahead.” Another stressed the importance of capitalizing on that sense of urgency: “It’s important that you don’t take the foot off the pedal. Stay engaged. . . . Ultimately, [the Basin situation] will reach a crisis stage. Unfortunately, when things reach crisis stage, we don’t always make the best decisions.” Several people conveyed a pressing need to “act, not study.”

Many people offered specific suggestions for priority actions, such as financial incentives for agricultural and urban water conservation and institutional changes to encourage strategic restoration of environmental flows. Others focused more broadly on policies aimed at encouraging movement of water to meet changing demands while maintaining lands in productive agriculture. Some emphasized the need to invest aggressively in new infrastructure to allow water to move between users and to develop new sources.

Virtually everyone emphasized the importance of engaging with one another beyond traditional boundaries, whether among user groups or across state lines and other political divisions. As reflected in our previous two reports on Colorado River management, many people are thinking about and pursuing cooperative solutions and would like to be part of a more deliberate, ongoing dialogue about such opportunities. Some credited the Basin Study with encouraging movement in this direction and are pleased to see a broader range of interests at the table now in Basin Study’s Work Groups and elsewhere, particularly representatives of Indian tribes and NGO stakeholder groups. Several people praised the Basin Study Work Groups for focusing attention on environmental flows and recreational uses of the river, as well as human and agricultural requirements, in its assessment of future water demands.

Even as people are working more cooperatively, they struggle with how to talk about the future of water in the Colorado River Basin. While most public discussions today focus on the projected imbalance of water supply and demand, several of the leaders interviewed for this report argued forcefully for approaching these issues through the lens of vulnerability, especially in light of climate change and increasing frequency of extreme weather events. They urge a greater emphasis on building resilience rather than augmenting water supplies to accommodate growth. Some say this conversation cannot occur without a fundamental reassessment of the Law of the River, although others point to the many ways in which this system of laws and policies has “flexed” over the years.

This report focuses on key themes, as represented by groups of solution options that received the most comments in this interview process.

Most people framed their comments around the options identified in the Basin Study, though their underlying concerns were broader—for example, ecosystem integrity and sustainable agricultural economies. The discussion in the section below titled “Mapping Solutions” highlights solutions grouped within the following themes:

- Voluntary and temporary water sharing transactions

- Broad water transfer mechanisms engaging water users over larger areas

- Urban water conservation and reuse

- Physical approaches to augmenting and managing water supplies

- Dialogue, coordination and education

Read the entire report at Mapping the River Ahead.